Developing the Home as an Alternative for Decongestion

We are engaging with hospitals to improve and increase Decongestion@Home.

If your organization is interested in preparing for change contact using the link below

Decongestion@Home

Outpatient Decongestion

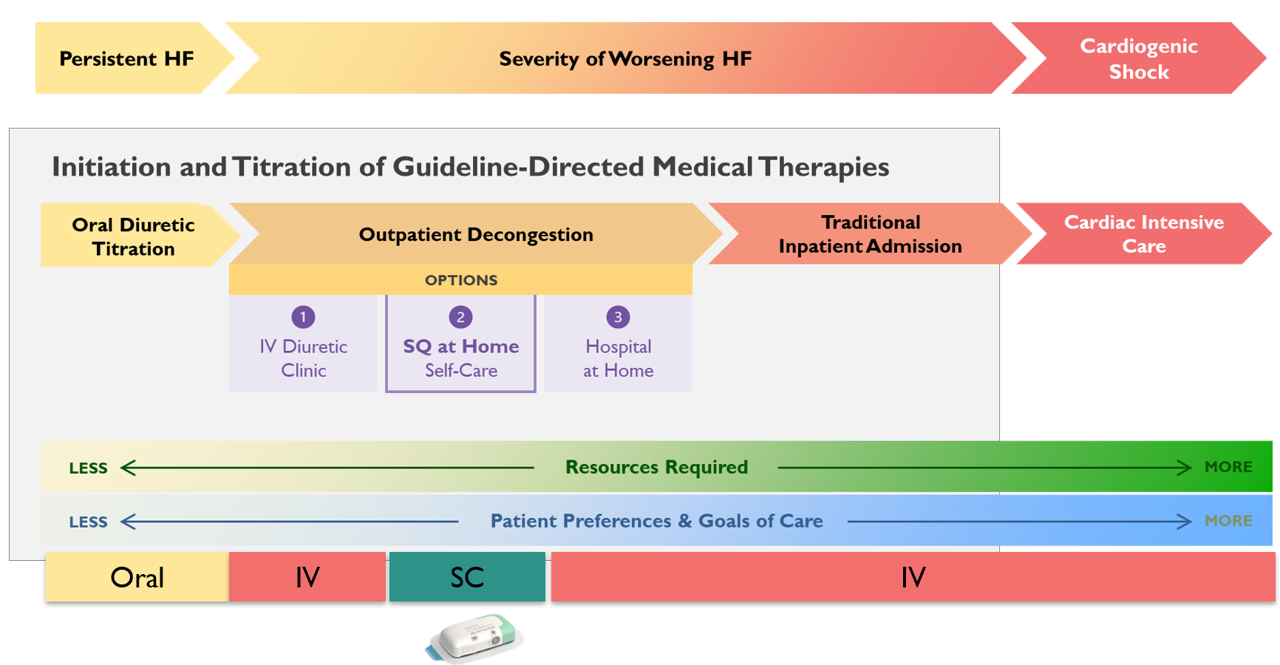

Outpatient Decongestion refers to using intravenous or subcutaneous diuretics to remove fluid overload in patients with heart failure or other conditions. There are three distinct forms:

- IV Diuretic Clinics – patient comes to the clinic for administration of a dose of IV diuretics – the patient stays in the clinic until the effect has worn off and it is safe to travel home again.

- SQ at Home (self-care) – patients often with the help of a caregivers uses one of novel the subcutaneous furosemide products at home as directed by a healthcare provider.

- Hospital at Home – the hospital provides a care team and services analogous to what a patient would receive in a hospital but now at home.

These three are all different and there is a place for all three. Subcutaneous furosemide at home is the emerging option. Lasix ONYU, when approved, would fit this option.

Treatment spectrum for worsening heart failure.

Important Differences

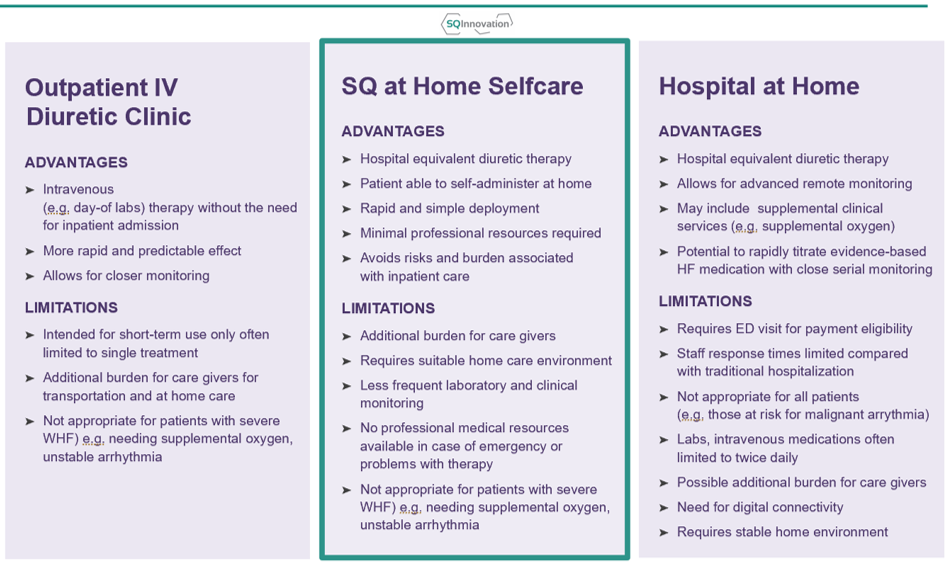

The decongestion at home options have different applications and benefits:

- IV Diuretic Clinics – In most cases a single dose is given. The patient does not return the next day. For most patients this is not enough and hence it can never be a replacement for a hospital stay.

- SQ at Home (self-care) – This is the newest option with the broadest use. However, the patient must have a good home care environment and in many cases some form of caregiver support is required,

- Hospital at Home – Although it offers distinct benefits over in-hospital care, it is as expensive and few places offer this and if so it is often limited to a few ZIP codes around the hospital.

Outpatient decongestion alternatives.

Timing is Everything

Worsening heart failure often develops gradually, with symptoms becoming noticeable only after significant fluid buildup. In the later stages, the condition can progress rapidly, and the most severe outcome is pulmonary edema. In the early stages, heart failure can often be reversed with oral diuretic adjustments, which is the most effective and cost-efficient option. However, if this approach fails or the condition has advanced too far, parenteral diuretics (IV or subcutaneous) are needed. If timely intervention is missed, the patient may develop pulmonary edema, which is a medical emergency requiring hospitalization. In such cases, the patient may need to be admitted to the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit.

Who is Eligible for Decongestion at Home?

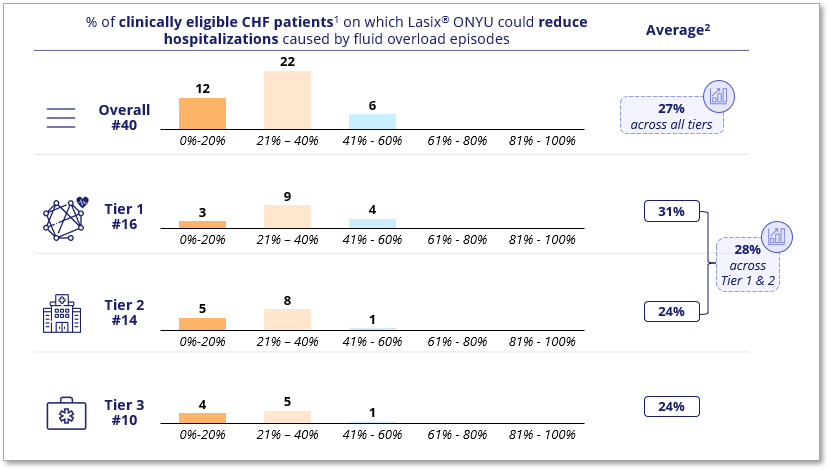

Outpatient decongestion is a rapidly evolving field. Two primary home-based options—subcutaneous furosemide and hospital-at-home programs—are still in their early stages and have seen limited adoption relative to their potential. This raises a critical question: what proportion of hospital admissions could these innovations prevent?

To explore this, we recently surveyed 40 heart failure programs spanning three hospital tiers. On average, clinicians estimated that 27% of patients currently hospitalized could be managed effectively at home.

We are continuing to investigate this important question, focusing on identifying the barriers to at-home treatment and exploring strategies to make outpatient decongestion the norm rather than the exception.

Results of a clinical intelligence survey conducted by AliraHealth (Framingham, MA), 2024

Breaking the Mold – Going Home Instead

In most cases, hospital admissions for heart failure start in the emergency department (ED). While it would be ideal to detect worsening heart failure earlier and initiate decongestion therapy without an ED visit, this is unlikely to become a reality in the near future. Therefore, widespread adoption of home-based decongestion strategies will likely require integrating the ED into a new “ED-to-home care” pathway for managing worsening heart failure.

This shift is less about the characteristics of specific therapies and more about the clinical processes of patient selection and management. Key elements include the ED-to-cardiology handoff, monitoring and follow-up, electrolyte management, and determining when to stop subcutaneous treatment. To address these challenges, we are collaborating with both the ED and heart failure communities to build consensus on these critical aspects.

How many Doses for Decongestion?

Answering this question is not straightforward. The treatment process is largely empirical—doses and durations are adjusted based on the patient’s response and individual needs. In the authoritative DOSE-HF study, patients in the low-dose group received an average of 358 mg of furosemide, while those in the high-dose group received approximately 773 mg over the three-day study period. Patients had received an additional 80mg prior to randomization and it is likely that many patients received additional doses after the study concluded and before hospital discharge.

Using standard 80 mg doses, this equates to about 4–5 doses on the low end and more than 10 on the high end. If treatment begins earlier—before the point at which a patient would typically be admitted—the required doses might be lower. However, there are also patients with significant fluid overload who need prolonged treatment to achieve their target dry weight.

When a hospitalization is replaced patients may require 4-5 80mg doses at the low end or over 10 doses at the high end.

Benefits Other than Financial of Decongestion at Home

Avoiding inpatient care is more than avoiding an expensive bill. Hospitalizations are especially hard on elderly patients. The elderly always lose muscle mass, often lose self-care functions and are at risk for complications from the stay.

Hospitalizations are not only costly; they also carry risks, including:

Infection

Older people are more likely to acquire hospital infections.

Delirium

Older people are prone to experiencing delirium during a hospital stay.

Immobility

Immobility may increase or aggravate skin problems including pressure ulcers.

Incontinence

40% – 50% of hospitalized patients aged 65+ are incontinent, many within a day of hospitalization.

Decline in Independence

12% of patients aged 70+ see a decline in their ability to undertake key daily activities (bathing, dressing, eating, moving around and toileting) during their hospital stay.

Muscle Loss

Older people have a lower muscle mass and experience a more rapid decline with bed rest. Elderly may experience a loss in muscle mass and strength of 11-12% per week as a result of bed rest. Reduced muscle mass results in a loss of function and self-sufficiency and an increased risk of falls.

Unnecessary Bed Rest

Patients who suffer from fluid overload generally do not require bed rest. Bed rest is the default position for someone who is admitted to an acute care hospital, regardless of whether bed rest is required for the treatment. This increases risks and adverse consequences that may be avoided with alternative therapies.

Disrupted Sleep

The hospital environment disrupts sleep patterns because of bright lights, loud machines, hallway conversations, regular status checks, and early morning blood draws.